Twitter Case Study: How to Design the Home Timeline for Massive Scale

Introduction

Twitter’s home timeline is in theory a very simple feature. Users are in a many-to-many relationship with other users. Users can post Tweets. Each follower of the user should see every Tweet posted by the people they follow in their home feed, sorted in chronological order.

The challenge for Twitter is building a highly-available and responsive home timeline given their massive scale. As of November 2012, Twitter had:

- 150M world wide active users

- Over 300K Queries-per-Second (QPS) for timelines

In conjunction with this scale, Raffi Krikorian notes in his QCon Talk that when a user tweets, their followers should be updated with the new tweet in 5 seconds or under. This article will explain why this is a non-trivial task and give a high-level overview of how Twitter designed their systems to accomodate their scale (as of 2012).

Approach 1: Naive SQL Query

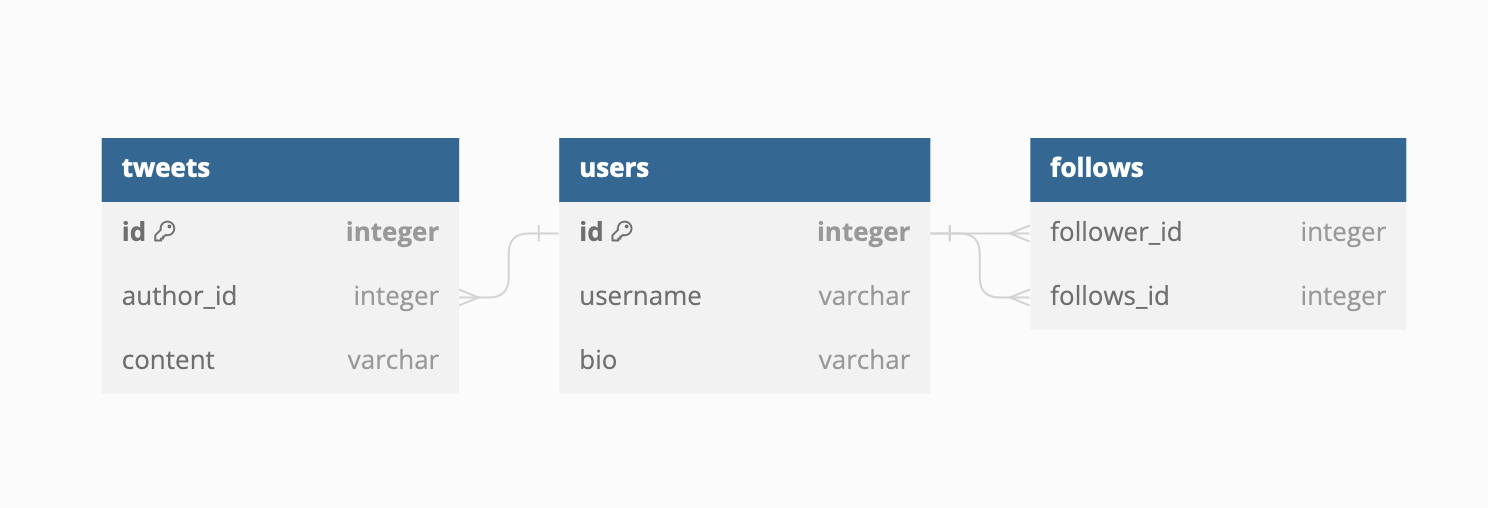

Below is a simplified SQL schema of Twitter’s data model.

Twitter’s initial naive approach was to join the Tweet, User, and Follows tables in SQL upon a GET request from a client like so:

SELECT * FROM tweets

JOIN users ON tweets.author_id = users.id

JOIN follows ON follows_id = users.id

WHERE follower_id = current_user.id;

You can quickly see how JOINing all Tweets with all Users and all follow relationships became quite slow at over 300K QPS.

Approach 2: Caching

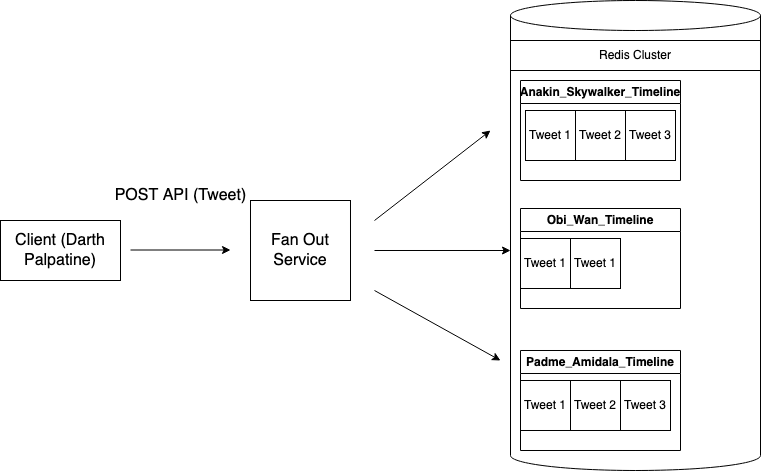

As a result, Twitter implemented a fan-out caching system. They stored a Redis list for each user containing the Tweets to display on each user’s home timeline (Redis is an in-memory data store. For more info on Twitter’s use of Redis, see here). Let’s illustrate this with an example. Say that Darth Palpatine is followed by Anakin Skywalker, Obi-Wan, and Padme Amidala. When Darth Palpatine posts a Tweet, Twitter’s fan-out service pushes the new Tweet to the Redis cache for each user that follows Darth Palpatine (Anakin, Obi-Wan, and Padme). This way, when Anakin (for example) loads his timeline page, his Tweets are cached in Redis and can be retrieved in constant runtime (in this simplified example).

The below system diagram presents a simplified version of this architecture. Note that several things are omitted for simplicity; for example the load balancer that receives the POST request from the client. Also note that the Redis Cluster is presented as one node in the diagram. In reality, a Redis Cluster (as the word “cluster” suggests) consists of lots of distributed Redis databases. In addition, Twitter (as of 2012) stores three copies of each Tweet across different Redis nodes to ensure system resilience and availability (as in a huge system like Twitter, nodes can frequently crash and become unavailable).

A system diagram of Twitter’s caching approach for home timelines.

A system diagram of Twitter’s caching approach for home timelines.

A Third Twist: the Hybrid Approach

The caching approach worked for accounts with a reasonable number of followers. Assuming an average follower count of 100 and 4.6k Tweets per second (based on November 2012 data), this translated to 460k writes per second to the Redis cluster.

However, for celebrity accounts with huge numbers of followers, this was not performant. A Tweet from Lebron James, who has 50 million followers as of 2023, would result in over 50 million writes at once. In this scenario, the caching approach was not feasible given Twitter’s goal of delivering Tweets within 5 seconds. As a result, Twitter implemented a hybrid approach, where most new Tweets were cached (using Approach 2) while Tweets from accounts with large followings were queried at runtime (like Approach 1) and merged chronologically with the Tweet cache.

To understand why the hybrid approach is better, we can broadly think about the advantages and disadvantages of Approach 1 and 2. Approach 1’s complexity increases as the size of our Users, Tweets, and Followers tables gets really large. However, the catch is that Twitter users don’t really follow millions of users so we only have to consider Users and Tweets. Approach 2’s complexity increases based on how many accounts follow you. We’ve established that Approach 2 isn’t the best with celebrities.

Now let’s consider the benefits of the hybrid approach over Approach 1. We can create tables CelebrityTweets and CelebrityUsers. When a user queries their homepage, we get from the Redis cache in O(1) runtime. Then we JOIN CelebrityTweets and CelebrityUsers to get any Tweets from celebrity accounts they might follow. Note that the size of CelebrityTweets and CelebrityUsers is quite limited relatively (compared to our original approach). Of course, given the popularity of Twitter, this hybrid approach might still have scalability issues. But the point of this case study is that the hybrid approach is much better than using Approach 1.

The exact implementation of this hybrid approach is beyond the scope of this article. However, this case study of Twitter illustrates some of the complexities systems encounter at massive scale. It also demonstrates how we should consider our goals (i.e. high availability) and use case (i.e. accounts with millions of followers) when designing systems.

Credits

This article is based on Raffi Krikorian’s November 2012 talk at QCon and Martin Kleppman’s book, Designing Data-Intensive Applications.